TL; DR: In his comic book-meets-manifesto “Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime,” Stanford Professor Ge Wang empowers readers to think bigger about the role of design in a highly technical era. As a multidisciplinary designer, engineer, and artist himself, the author is right at home pushing aside traditional intellectual boundaries to investigate the aesthetic and ethical aspects of technology. In doing so, he proves that it can be used as a medium to do good. Through works like the ChucK music programming language, Stanford Laptop Orchestra (SLOrk), and iPhone-based Ocarina, Ge illustrates how artfully designed technology can help satisfy the human desire to be understood.

The ocarina, an oval-shaped flute, dates back more than 12,000 years, when ancient civilizations handcrafted them out of clay, wood, and bone.

The intricate detailing on some of these artifacts — formed into animals, people, and pendants — is a sight to be seen. Still, one of the most fascinating aspects of these primitive instruments lies in what they meant to the humans who played them.

Ocarinas were notably significant to the Mesoamerican and Chinese, who used the wind instruments as an ambient backdrop for entertainment and religious rituals. Italy’s Giuseppe Donati modernized the instrument in 19th-century Europe, where it was used to engage audiences during solo and group concert performances. By the 20th century, the U.S. Army issued spirit-boosting ocarinas to troops serving in World War II.

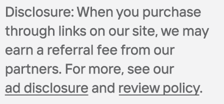

Today, the history of the ocarina is still in the making. With the Ocarina app, for example, users can transform an iPhone into an instrument that responds to breath, touch, and movement. And, like previous incarnations of the ocarina, this smartphone-based version is already making an impact on humanity.

“This is my peace on earth,” wrote a U.S. soldier in a June 3, 2009, App Store review of Ocarina. “I am currently deployed in Iraq, and hell on earth is an everyday occurrence. The few nights I may have off, I am deeply engaged in this app. The globe feature lets you hear everyone else in the world playing in the most calming art I have ever been introduced to. It brings the entire world together without politics or war. It is the EXACT opposite of my life.”

The brains behind the app, Stanford Professor Ge Wang, told us that technology in some shape or form has always been used to make instruments — today, it’s just highly programmable. And Ocarina is just one part of his multidisciplinary exploration of artful design.

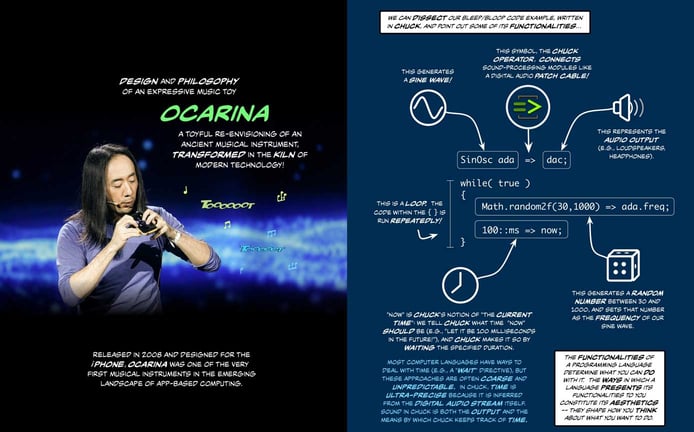

The phenomenon, both a concept and the title of his vividly illustrated book, “Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime,” delves into how technology, initially shaped by humans, ultimately shapes humanity.

In the comic-inspired book, Ge uses his own creative endeavors — instrument-app hybrids like Ocarina, a music-oriented programming language, and a modern laptop orchestra — to explore the convergence of technology, design, and humanity.

The things we design with technology, he said, design us. Therefore, at the heart of artful design is an important ethical question.

“How do we want to live with our technologies? That’s the question that every human being on this planet has to confront, just by virtue of being human and also being a part of society,” Ge said. “When you zoom out, artful design is not really about computer music at all.”

A Fresh Engineering Perspective

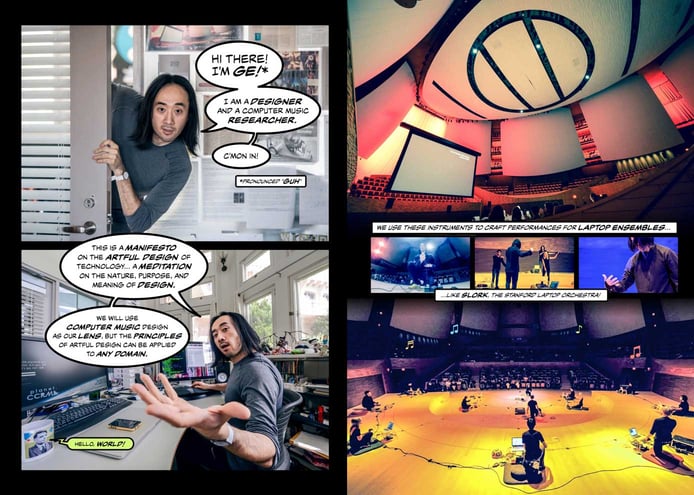

Ge works as an associate professor at the Stanford Center for Computer Research and Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), pronounced “karma.” He researches the many facets of artful design, from music-oriented software and programming languages to virtual and augmented reality. He also directs the Stanford Laptop Orchestra (SLOrk), a computer-powered take on conventional ensembles.

“I make things, I build things, I design things,” Ge said. “I design tools, software instruments, social experiences, VR, and artificial intelligence systems. And software is my tool. Our go-to tool in the Stanford Laptop Orchestra is an open-source music programming language called ChucK.”

Ge created the programming language as a graduate student at Princeton University working with computer music researcher and professor Perry Cook. As co-founder of the mobile app development company Smule, Ge built Ocarina and the app Magic Piano. He wrote both using ChucK.

Ge said that most of the sound produced from the laptop orchestras at Stanford and Princeton is a product of the programming language. He uses ChucK himself when teaching multiple courses at Stanford.

Underlying all of Ge’s work, of course, is a laser-like focus on artful design.

“I was trained as a computer scientist, so the engineering way of thinking is very familiar to me,” he said. “But I subscribe to a different kind of engineering mentality — one which is not always problem-driven but values-driven. We think music making is good, and that’s enough to start making things, even if nobody asked for them.”

Directing the Stanford Laptop Orchestra

The team at CCRMA built the Stanford Laptop Orchestra in 2008 using everyday materials like laptops, IKEA salad bowls, amplifier kits, auto speakers, and meditation pillows. But the idea originated with Ge’s advisors at Princeton, who started the Princeton Laptop Orchestra (PLOrk) in 2005.

“When I became a faculty at Stanford in 2007, I basically brought the idea with me and started a West Coast sibling,” he said. “We’ve made close to 300 original pieces, with almost as many new, bespoke instruments.”

With traditional instruments — the violin, for example — that evolve slowly over time, designers must create a solution that works in numerous musical scenarios. But as Ge learned at Princeton, the opposite is true when transforming a laptop into an instrument.

“In fact, you can make an instrument that works really well for just a single piece of music,” he said. “My advisor at Princeton, Perry Cook, said, ‘Don’t make an instrument, make a piece. Figure out what instrument fits that piece, and then design that instrument.’”

The creative works born from SLOrk illustrate the power of this methodology. For example, in Aura (2019), CCRMA Ph.D. student Kunwoo Kim sought to emulate invisible human energy fields.

To do so, he designed SLOrk musical lanterns (SLanterns) that used accelerometers to communicate wirelessly with laptops. Via the ChucK programming language, performers could then tell a musical story by dictating changes in music, light, and a full range of RTB colors.

The Future of Music & the Pi Shaped Student

When it comes to the music of tomorrow, Ge envisions a nearly limitless creative landscape. “There’s no one single future of music, in my opinion; it’s going in a million different directions all the time,” he said. “And I think that’s actually, on the whole, really wonderful.”

To that end, the SLOrk crew plans to push the boundaries of the laptop orchestra moving forward by exploring emerging technologies.

“I’ve been a venture-backed startup cofounder and a professor, and the blessing of being in academia is the sheer freedom and experimentation we are given to make interesting things. It’s still early, but we’re thinking about things like music-making with VR in a group setting.”

Ge’s future goals as an educator involve a focus on the ethics of technological design.

“Understandably, people are worried about the harms of technology,” he said. “From social networks to AI, there are a lot of ways that we could shoot ourselves — not just in the foot but in the head. And while ‘do no evil’ is a good baseline, there has to be more than that.”

In leading the future generation of artful designers, Ge advocates for a holistic approach to engineering education. Many thought leaders use the metaphor of an I-Shaped versus T-Shaped student when describing breadth or range. I-Shaped individuals are narrowly focused on one disciple, while T-Shaped students specialize in one discipline but have some knowledge in another area.

Through “Artful Design,” Ge fleshes out another option: the higher education concept of the Pi-Shaped individual.

“One leg of the pi symbol is disciplinary expertise; for me, that was computer science,” he said. “The other leg is domain expertise, which is what you apply your discipline to. For me, that is music; for another person, it could be public health.”

The top bar of the pi symbol represents what Ge refers to as the aesthetic lens. “It’s a philosophical, artistic, and moral lens that gives broader meaning and context in bridging the two legs.”

As an educational mission, Ge aims to encourage engineers to take supplemental classes on topics like humanities, philosophy, literature, music, art history, social science, cultural anthropology, sociology, and media studies.

“The laptop orchestra, in a way, represents all of these underlying currents — and that’s part of why we’re doing it.”

HostingAdvice.com is a free online resource that offers valuable content and comparison services to users. To keep this resource 100% free, we receive compensation from many of the offers listed on the site. Along with key review factors, this compensation may impact how and where products appear across the site (including, for example, the order in which they appear). HostingAdvice.com does not include the entire universe of available offers. Editorial opinions expressed on the site are strictly our own and are not provided, endorsed, or approved by advertisers.

Our site is committed to publishing independent, accurate content guided by strict editorial guidelines. Before articles and reviews are published on our site, they undergo a thorough review process performed by a team of independent editors and subject-matter experts to ensure the content’s accuracy, timeliness, and impartiality. Our editorial team is separate and independent of our site’s advertisers, and the opinions they express on our site are their own. To read more about our team members and their editorial backgrounds, please visit our site’s About page.